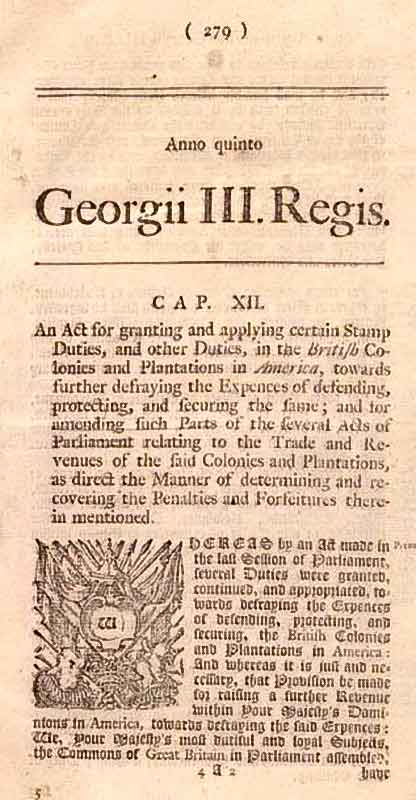

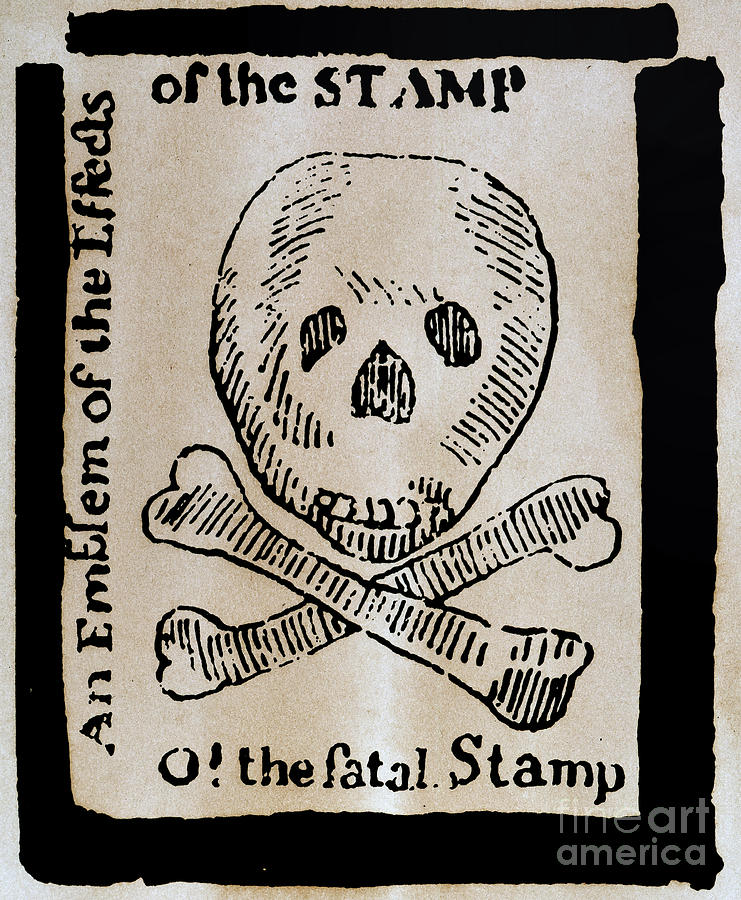

In February 1766, Parliament voted to repeal the Stamp Act. Although British officials dismissed the Congress as an extralegal body, they could not ignore the economic damage done by the boycott. In October of 1765, in an unprecedented display of colonial unity, thirty-seven delegates from nine colonies gathered in New York City for the Stamp Act Congress, which issued these resolutions and sent petitions to the king and both houses of Parliament. They boycotted goods subject to the stamp tax ostracized and intimidated stamp tax collectors and protested, petitioned, and organized resistance not only on the local level but also through an intercolonial network of activists known as Sons of Liberty. By reaching into Americans’ pockets without their permission, it had committed an act of theft.Ĭolonists did not take kindly to what they perceived as this violation of their rights. If the protection of private property stood as one of the first goals of government-a premise the colonists thought England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688–89 had sanctified-then the British government was not merely failing to do its job. Even worse, the Stamp Act amounted to taxation without representation since Parliament included not a single member elected by Americans. It was bad enough that this measure increased taxes and required payment in hard-to-find British currency. In 1765, hoping to boost revenue, Parliament imposed on its colonies the Stamp Act, which taxed everything from contracts to newspapers, stationery, playing cards, and dice. During the course of the Seven Years’ War, as this conflict was known globally, Britain’s debt doubled. The stunning irony of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), which resulted in Great Britain gaining from France a vast North American empire, is that it set in motion events causing Britain to lose that hard-won empire-as well as the thirteen Atlantic seaboard colonies that had contributed mightily to its victory.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)